Is Tropical Milkweed Bad for Monarchs?

Like a lot of Floridians, I got into gardening during the pandemic. Over the course of six months, I went from watching a YouTube video about tomatoes to converting my front yard into a food forest. I’m up to 11 raised beds, 50 containers, and a small grove of tropical fruit trees. I’m my neighborhood’s crazy plant lady and I love it.

I’m always on the lookout for new babies to add to my collection and sometimes I find them in unsuspecting places. One of these places was at a local festival called Art Crawl. The City of Lakeland had a booth filled with free plants and it was there that I snagged some tropical milkweed. I figured this pretty plant would be the perfect addition to my butterfly garden.

I took my free milkweed home, threw it in a bigger pot, and a few months later the leaves were dripping in monarch caterpillars. It worked! My heart was full and I felt like I was making Captain Planet proud.

But wait. If monarch caterpillars swarmed my tropical milkweed, then why I’m urging you to ditch this plant?

I’m learning as I grow and while doing research, I found that many scientists around the country are asking Floridians to stop growing the non-native tropical milkweed because it’s a breeding ground for a butterfly parasite called Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, or OE for short.

OE lives as a spore on the tropical milkweed plant and when a monarch caterpillar eats OE-infested leaves, it too gets infected.

A monarch caterpillar infected with OE may not have enough strength to escape from its pupa after it turns into a butterfly. If an infected monarch does make its way out of the pupa, it might be deformed and even if it isn’t, there’s a good chance it’ll die during its winter migration to Mexico.

Tropical milkweed can also alter the monarch migration pattern. Perpetual growing tropical milkweed gives the monarch butterfly a year-round source of food. Although that sounds like a good thing (who doesn’t like a 24/7 buffet?), it can stop them from migrating since they have no reason to leave.

Gardeners in cooler climates don’t need to be as concerned with this problem, but it should be on the Floridians’ radar. Tropical milkweed dies back in frost and when the milkweed dies, the OE goes with it. Since it rarely gets cold enough in Central and South Florida to kill tropical milkweed, OE builds up on the plant over time.

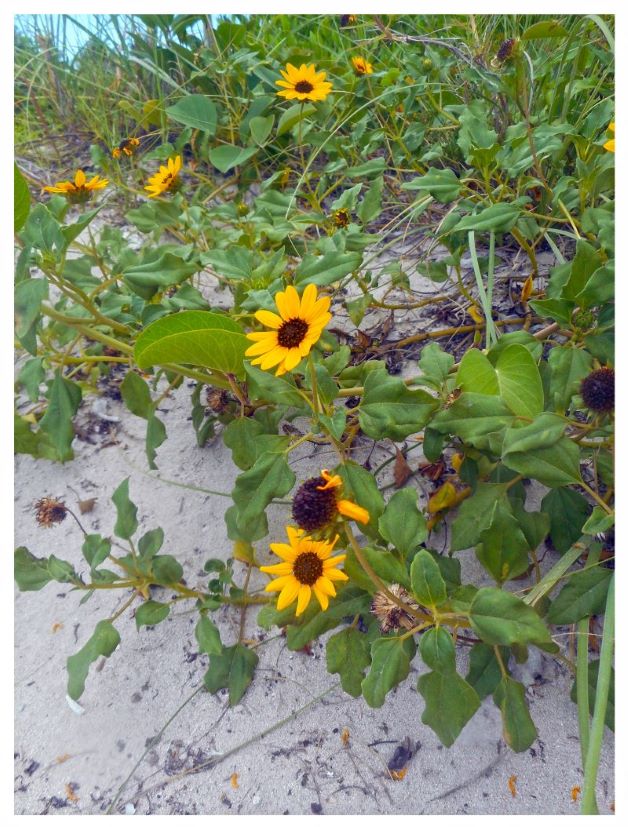

Does this mean that Floridians are doomed to maintain a butterfly-free yard? Nope! There are 21 species of Florida native milkweed, and all make a great host plant for monarchs. Native milkweed dies back after blooming and we know that this life/death cycle helps to keep OE levels down.

For an easy fix, swap out your tropical milkweed with the Florida native orange butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa). Visually speaking, it’s close to a dupe.

Floridians can also cut back their tropical milkweed down to the stems every fall. This will destroy any infected milkweed leaves and new, fresh leaves will emerge in spring. If you don’t want to bother, though, replace your tropical milkweed with native.

This milkweed mishap taught me something important: changes in our environment, however small, can have big consequences. If you have the choice, always plant native species. The less we meddle with Mother Nature, the healthier our plants (and the critters that live among them) will be.